| Search PNC News for stories of people and churches in our UCC Conference: |

|---|

Congregation’s founding story stirs reflections

Since he came as pastor of Westminster Congregational UCC three years ago, Bob Feeny has expanded his awareness of indigenous history and colonial impacts.

|

Bob Feeny, pastor, and Mary Rupert, member of Westminster Congregational UCC in Spokane plan a winter series to continue exploring colonization and indigenous people. |

The church participated last fall and winter in a study, “Wrestling with the Truth of Colonialism,” offered by the Truth and Transformation Team of the Spokane Alliance. About the same time, Mary Rupert, a 20-year member, began sharing research she had done looking into the context of the church’s founding story. Last spring, several members gathered to discuss the name of their Mayflower Room.

From Jan. 7 to March 7, Westminster will offer a Zoom series for its Tuesday Night Talks on “The Land Is Not Our Own: Seeking Repair Alongside Indigenous Communities.” The eight-week series is developed by JustFaith Ministries in collaboration with The Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery.

“Its goal is to equip congregations to stand alongside Native communities in working for justice and repair,” said Mary, anticipating that the process will lay a foundation for trust and relationships so participants can acknowledge injustice, honor the interconnectedness of Creation and seek healing, repair and hope.

|

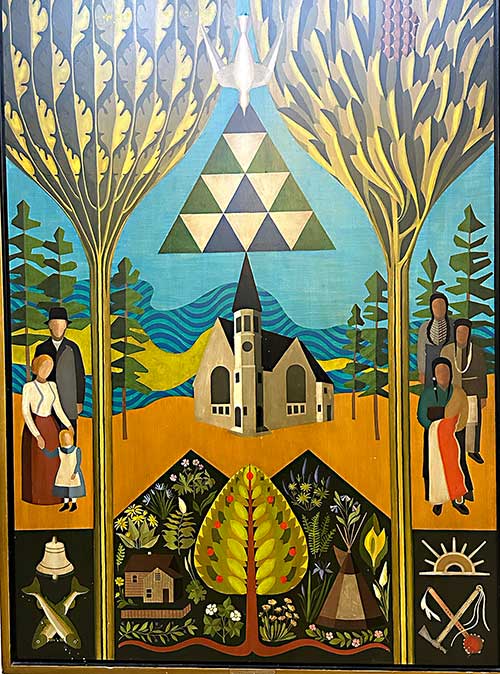

A 1968 painting in Westminster UCC’s fellowship hall depicts the story of missionary Henry Cowley establishing First Congregational Church in 1879 with Spokane Indians to serve both Indians and white settlers. |

The series will take participants through lament as they hear historical truths related to how the Doctrine of Discovery generates power and wealth as it permeates U.S. laws and Church policies. The sessions also invite hope, joy and healing, celebrating Indigenous artists and activists, honoring the sacred connection of Creation and learning ways to partner with Native leaders in work for justice and repair.

The class is based on a book by Sarah Augustine, who says, “What was done in the name of Christ must be undone in the name of Christ. The good news of Jesus means there is still hope for righting of wrongs.”

The cost of the curriculum and books for this class is covered by a grant from the PNC-UCC. Mary and Bob will co-teach the class.

Mary’s interest in the Indigenous neighbors grew from her curiosity about Westminster’s founding story in which two of its founding members were Spokane Chief Enoch Siliqouwya and his wife, Anna. They joined with missionary, the Rev. Henry Cowley, whose biography, entitled “A Tepee in His Backyard” by Clifford Drury, document’s Cowley’s relationship with the Middle Spokane band.

Knowing of the hanging of Spokane Indians and the massacre of their horses by General George Wright, Mary wanted to know more about the context of their relationship and began researching more about the history, aware there are no current indigenous members.

Pastor Bob grew up in New Hampshire until he graduated from Plymouth State University in 2010 with a bachelor’s degree in American literature and film. During those studies he began to understand the brutality of colonization.

“As I started to grapple with the reality of American history, the ugly history related to colonists and indigenous people became clear,” said Bob, who opens worship with an acknowledgement that the land on which the church gathers to worship was stewarded by the Spokane people who suffered from genocide. Each week he calls for those gathered to work together with the Indigenous people of the area for justice.

He believes there is need to have a reckoning with “the way we went about colonialism” that was “disconnected from land and all creation.”

In university studies, Bob first engaged with early indigenous writings and became curious about indigenous history. .

After working in college housing for five years, Bob went to Chicago Divinity School, where he learned more of Indigenous people from a classmate who served a church on a reservation and from protests at Standing Rock.

In 2019, he graduated and served a UCC church in Massachusetts, drawn to the UCC in college by its progressive Christianity that contrasted with his experiences growing up in a Pentecostal church.

Since coming to Spokane, he has found Indigenous communities prominent, present and powerful in this region.

He notes that the story of the Cowleys founding the church with Chief Enoch and Anna, may have comforted some.

“The story of the church’s founding is true, but in the broader context, it was still connected with colonization,” he said. “Cowley may for his time have been more sensitive to Indigenous people than other settlers. From all accounts, he did not want to destroy indigenous people, which some openly said they wanted to do,” Bob said. “He was still part of the system.

“For Christians, we need to recognize that no matter what we do or how we act, we are implicated in the big story,” he continued. “Christianity is a story that has had profoundly positive impact in many cultures and many lives, and it has also been party to some truly horrific things.”

Bob noted that Christianity has sometimes been destructive of lives and cultures, like with the Doctrine of Discovery or making it illegal to do indigenous religious practices until the 1970s.

“We cannot separate ourselves from that element of Christianity,” he said. “The UCC has a long history on this continent and with the indigenous people of Hawaii, where it has done some work at telling truth and doing some repair.”

Mary commented that the UCC didn’t rescind the Doctrine of Discovery until 2016.

“Most weren’t even aware of it, but the Anglican church in Canada, where I grew up in Ottawa and Vancouver, rescinded it in 1996,” she said.

“People say we aren’t responsible for what happened back then. That’s true, but we need to take responsibility for what is happening now, and we can see, own and understand what happened,” she said. “Similar genocide has happened around the world, and we need to understand our own place in it, so we don’t continue to do that forever.”

Bob pointed out that how people tell stories about what has happened impacts how they think and live now.

“Humans are rational creatures but also myth making creatures. Life is based on the stories,” he said. “Science tells how we are here and what we are made of, but the decisions we make about how we live relate to why we think we are here.

“Most have a story. Some tell it in theological language and some mythically. Stories give us purpose and drive. If the story is based on the assumption that we have a divine right to be here and own the land, we may carry out terrible things, said Bob, who is struck by indigenous people talking of a way of belonging to the land rather than talking of land belonging to them. “Belonging to the land is hard for some brains to understand.”

Before Thanksgiving Bob explained that Thanksgiving is a cherished tradition for many coming from a “tidy story” that includes Thanksgiving myths.

Ancestors who came for freedom were welcomed and helped by the Indigenous people of Turtle Island, but they did not “live happily ever after.”

Bob pointed out that while some colonists came for religious and political freedom, others came for economic opportunity. Some were children and had no choice.

“We cannot readily know every single person’s motivation for coming, but we can assume that like at every Thanksgiving Table, there were kind, loving people, and there were mean, cruel, hateful people,” Bob said.

“We cannot know the intentions of every person who came, but we can know that when the Mayflower landed on Nov. 21, 1620, a brutal process of colonization followed,” he said.

Bob pointed out that some native tribes welcomed the Pilgrims and some resisted. There were kind colonists and genocidal ones, the latter shaping colonial policy.

“As members of the United Church of Christ, we are descendants of the Mayflower—a fact memorialized in the name of the Mayflower Room. Under the Doctrine of Discovery and girded by the belief that this was their Promised Land—to be taken by brute force—our ancestors carried out horrific acts of violence against indigenous peoples in colonization, against Black bodies, forcibly brought to this continent as slaves, against innocent women lynched in the Salem Witch Trials, and countless more,” Bob said. “We cannot change that, nor should we deny it.”

Recently some church members met to discuss that the church has a Mayflower Room, when Mary wondered if indigenous people would be offended by that name.

She realized that some would be, but others would say, “Forget about a room’s name. Help us fix the justice system, the school system, the foster care system, fix the Missing Murdered Indigenous Women/People system, fix the systems that are screwing us.”

Bob agrees it’s important but not to turn a concern into naval gazing. To change the name of a room might mean spending time talking about it and making a decision.

“I think discussion is important. Names matter. It matters what we lift up and memorialize and what stories we tell but if we change the name and think we are done with it feels wrong,” he said.

Awareness of why predecessors called it the Mayflower Room can have value, he said.

“Aspects of the story of the Mayflower are inspiring. People set out on a voyage and that took courage, but the outcome for indigenous people was not good,” Bob said. “Many were good, kind people, but I’m not looking for evidence to exonerate what happened because of colonization.

Mary said that looking back at history, “we don’t understand all the complexities. I have traveled around world and there are good people and bad people everywhere I’ve gone,” said Mary.

Bob noted that within the big story of European colonizers acting in certain ways, there were always people pushing against those cultural norms and advocating for change.

“We can choose which stories we tell. We can give thanks for the voices that have always called for humanizing one another,” he said. “We can learn to see the powerful indigenous resistance to colonization that continues to this day, as a legacy to lift up along with the stories of our ancestors. We can write new stories, and new possibilities, even as we remember the past—in all its complexity.

“We need to see the balance between the grand sweeping narrative and threads of the story that make it all up,” Bob said.

“Sometimes it’s about being in relationship and that takes time,” he said. “For the church, we need to continue to learn our history and tell a story that’s truer. We also need to find ways we may be in more meaningful relationship with Indigenous people and communities.”

For information, call 509-624-1366 or email pastorbob@westminsterucc.org.

Pacific Northwest Conference United Church News © December 2024